report

The 2022 City Violence Prevention Index

Introduction

A Message from Greg Jackson

Dear Readers,

Almost four years into a global pandemic, communities across the country have become all too familiar with public health emergencies, epidemics, and the vital role local, state, and the federal governments play in developing and implementing public health strategies to save lives.

We know that our governments are equipped with the tools and resources to effectively address the gun violence epidemic plaguing this country. Our leaders just have to approach this problem with the same level of urgency, intensity, and resolve afforded to other epidemics and public health crises. The nationwide response to COVID-19 is just the latest example of decisive action needed to drastically improve outcomes in communities experiencing the worst effects of a public health crisis. Yet, decade after decade, the American gun violence epidemic has continued unabated, and, in recent years, grown to record levels.

Gun violence disproportionately plagues communities of color at alarming rates, taking the lives of thousands and altering the lives of millions of families who live with the lasting mental and emotional trauma of daily fear and grief. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the firearm homicide rate increased about 35% overall between 2019 and 2020, and the largest increase in firearm homicides was among Black people (39%).[1] Today, gun violence remains the leading cause of premature death for Black men, as well as the number two cause of premature death for Latino men and Black women.[2]

Since our founding, Community Justice has been dedicated to building community power to reduce gun violence, especially in Black and Brown communities most impacted due to the compounding effects of generational trauma, systemic racism, and devastating divestment in our communities. As the gun violence epidemic continues to wreak havoc on families and communities nationwide, local officials must take responsibility and implement comprehensive community-based violence prevention strategies that are anchored in a public health approach.

For decades, courageous survivors and advocates have led highly impactful efforts to interrupt cycles of violence and save countless lives in their communities with little or no support or funding from their governments. This lack of support must end.

While states and the federal government play essential roles in addressing the gun violence epidemic, cities can and must spearhead community violence intervention strategies and investments using the many levers of local government at their fingertips. Mayors, city councils, city managers, city attorneys, city offices of violence prevention, and local health departments must make good on their primary duty of protecting the health, safety, and well-being of the communities they serve.

This is why we created the City Violence Prevention Index, the first and only national assessment of local programs, services, and policies that work together to effectively reduce gun and other forms of violence. These strategies and policies are evidence-based, community-based, and driven by a public health approach. This report – and the metrics by which cities are assessed – represents a holistic toolkit for city officials, local advocates, and community organizations working to end violence.

As a Black man and a survivor of gun violence, I look forward to the day when all of our communities, and especially Black and Brown communities, are no longer devastated by the lasting intergenerational trauma engendered by gun violence and the ongoing systemic inequities that fuel this epidemic. I am hopeful that this annual report makes clear how much work we have left to do to get us there, and that it inspires you to fight for these lifesaving programs and policies in your community.

Sincerely,

Greg Jackson

Executive Director, Community Justice Action Fund

Why a Violence Prevention Index?

Despite the fact that violence was first recognized federally as a public health concern in 1979, many cities across the country have yet to begin funding comprehensive public health strategies to end the cycle of violence that disproportionately devastates Black and Brown communities. The City Violence Prevention Index is a first-of-its-kind report that provides city officials with a framework for investing in a comprehensive public health approach to violence prevention. It allows local officials to understand the current extent of their violence prevention investments and infrastructure, identify priorities for expanding their violence prevention initiatives, and track their progress over time.

Frequently Asked Questions

Community violence intervention or community-based violence intervention (CVI) is a key component of a public health response to violence. CVI programs rely on “credible messengers” who often hail from communities that experience high levels of gun violence to directly connect and form relationships with individuals identified as high risk for engaging in or experiencing violence. Credible messengers leverage these relationships to prevent violence by mediating conflicts, negotiating cease-fires, and connecting at-risk individuals with wraparound services and supports.

CVI strategies are assessed in the Intervention section of Part I of the City Violence Prevention Index scorecard and include outreach-based violence intervention, hospital-based violence intervention, and cognitive behavioral therapy-integrated mentorship programs.

The City Violence Prevention Index (VPI) is a first-of-its-kind national examination of local violence prevention programs, services, and policies. In addition to capturing the extent of cities’ current violence prevention strategies and funding, this report will allow cities to track their progress on violence prevention investments over time and identify annual violence prevention priorities.

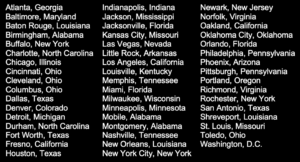

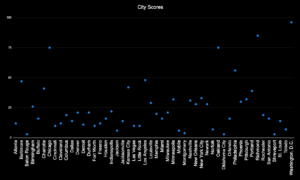

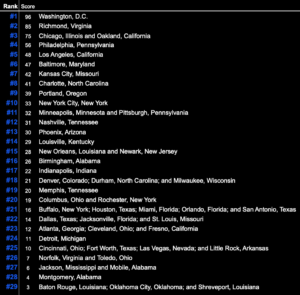

This inaugural edition of the VPI rated the 50 U.S. cities (including Washington, D.C.) that experienced the highest incidents of fatal and nonfatal gun violence in 2021 based on data from the Gun Violence Archive, an independent nonprofit organization that collects data on gun violence incidents from over 7,500 law enforcement, media, government, and commercial sources daily.

As a federal territory, Washington, D.C., is neither a city nor a state. Since Washington, D.C., falls within our city selection criteria and performs some functions of a municipality, we included it in this report.

The VPI scorecard is composed of 35 recommendations that form the framework of a comprehensive public health response to violence. These criteria cover the following areas: immediate intervention, risk factor reduction, housing and food insecurity, employment, education, health, youth and families, firearm laws and regulations, crime reporting and data, and offices of violence prevention. If a city meets the standards for credit for a category, the points assigned to that category are added to the city’s total score. Some criteria allow for partial credit to account for variations in local authority and city advocacy against state restrictions or in support of state and federal solutions.

The VPI scorecard reflects 106 total raw points, but all final scores are capped at 100 points. This scoring structure prevents localities from being penalized for criteria that are outside of their legal authority.

Next year, an additional metric assessing whether cities meet minimum funding levels for community violence intervention programs will be added to the scorecard. More information on this upcoming category can be found in the Standards for Credit section.

No. Since many states prohibit cities from regulating firearms to varying degrees, cities are not penalized if they do not meet the standards for ghost gun prevention ordinances and background check and permit-to-purchase requirements. Moreover, cities that publicly push back against state-level restrictions or advocate for state-level solutions are recognized with partial credit in these two sections of the scorecard.

Cities rated in this report were notified in May via email and/or certified mail (to mayors’ offices, city managers’ offices, and city offices of violence prevention where established). The Community Justice team researched publicly available resources, including city websites, municipal codes, and other online resources to compile draft scorecards, which were sent to cities in July via the same methods and to the same offices noted above. Cities were given four weeks to email requested changes and supporting documentation for our team to review. Finally, cities were notified ahead of this report’s release.

This report only examines whether a city contributes some funding to rated violence prevention programs and does not currently track precise funding levels for individual programs and services. Additionally, the VPI does not examine the quality of city-funded violence prevention programs or the quality of a city’s implementation of an assessed law or policy. The VPI does, however, assess whether local offices of violence prevention regularly assess the quality and efficacy of city-provided and city-funded violence prevention programs.

Public Health Approach & City Role

Every year, over 110,000 Americans are shot and more than 40,000 die from gun violence.[3] The most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shows troubling increases in homicides across the country in 2020.[4] And for the first time ever, gun violence became the leading cause of death for children and teens in the U.S, surpassing car accidents, drug overdoses, and COVID-19.[5]

Due to the lasting impacts of historical and persisting systemic racism and inequities, Black and Brown communities are disproportionately impacted by violence. According to the CDC:

- Black, Indigenous, and Latinx people have higher homicide rates than other racial and ethnic demographic groups.[6]

- Between 2019 and 2020, the largest increase in firearm homicides was among Black people (39% increase), and the largest increase in firearm suicides was among Indigenous people (42% increase);[7] and

- Gun violence remains the leading cause of premature death for Black men, as well as the number two cause of premature death for Latino men and Black women.[8]

This crisis cannot be abated by systems that are only designed to respond to violence after it occurs. Addressing the gun violence epidemic requires cities to commit to long-term investments in public health strategies that prevent violence before it occurs and tackle the root causes of violence.

The Public Health Approach to Violence Prevention

Violence was first recognized as a public health issue by the U.S. Surgeon General in 1979.[9] Public health draws on science and expertise from a broad range of disciplines and emphasizes input from diverse sectors, including health, education, social services, policy, and the private sector.[10] Applying the public health model to violence prevention means utilizing the same data- and science-driven process used by public health experts to tackle all public health matters.

At its core, this approach consists of the following four-step process rooted in the scientific method: (1) Defining and Monitoring the Problem (e.g., violence prevalence, frequency, locations, victims and perpetrators, and trends); (2) Identifying Risk Factors (which increase the likelihood of a person experiencing or engaging in violence) and Protective Factors (which decrease the likelihood of an individual experiencing or engaging in violence); (3) Developing and Testing Prevention Strategies; and (4) Assuring Widespread Adoption.[11] When backed by sufficient and sustained public investments and resources, the public health approach to violence prevention has been shown time and time again to be effective in significantly reducing violence.[12]

Community violence intervention (CVI) is an essential part of a comprehensive public health approach to violence prevention. This strategy utilizes professionally trained “credible messengers” — also known as “violence interrupters” — to go into communities that are disproportionately impacted by violence, form relationships with individuals who have been identified as high risk for engaging in and/or experiencing violence, and leverage their relationships and personal experiences to intervene in and prevent potentially violent situations. Credible messengers employ mediation techniques to negotiate cease-fires between individuals and groups and provide personal mentorship and support to help shift the culture of conflict resolution away from violence. Violence interrupters play a central role in numerous strategies assessed in the City Violence Prevention Index (VPI), including outreach-based violence intervention (also known as street violence intervention), hospital-based violence intervention, and cognitive behavioral therapy-integrated mentorship programs. They also help link victims and survivors of violence with essential services and supports, including trauma-informed behavioral and mental health care, financial assistance, and legal aid.

Importantly, CVI strategies must be implemented alongside long-term preventive strategies designed to address the upstream root causes of all forms of violence, including family violence, intimate partner violence, and suicide.

The Role of City Government

One of the challenges communities face in advocating for local investments in public health violence prevention strategies is the deferral of responsibility by local leaders to higher levels of government. While states and the federal government play essential roles in addressing the gun violence epidemic, city officials can and must utilize the many resources and levers of local government to implement these livesaving programs, services, and policies.

Mayors, city councils, city managers, city attorneys, local health departments, and school boards must work together with urgency to combat this public health crisis. Local officials are best situated and most qualified to lead violence prevention efforts, given their unique knowledge of and proximity to the communities most impacted. Furthermore, local agencies collect and have access to the violence-related data needed to develop effective, targeted intervention strategies.

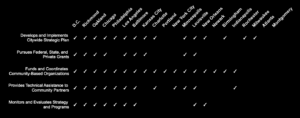

Funding

The majority of the VPI scoring assesses city spending to determine whether cities directly provide or fund the evidence-based programs and services included in this report. The following outlines ways that cities can fund these lifesaving initiatives, all of which are recognized in the VPI scoring process.

- Cities must consistently appropriate adequate general funds for CVI and other public health-based violence prevention programs through the annual budgeting process.

- Municipal officials must exercise the discretion they have over certain state and federal funds (like American Rescue Plan Act funds) to invest in VPI-assessed programs and services. Moreover, as federal funding from the recently passed Bipartisan Safer Communities Act makes its way to cities, local leaders should ensure that those funds support the evidence-based initiatives outlined in the VPI scorecard.

- Cities that have their own health department should develop and fund a robust health department-wide violence prevention strategy that fits into their broader city government-wide violence prevention strategy.

- Cities that do not have their own health department should collaborate with county health departments to develop a county health department-wide violence prevention strategy. Additionally, cities can provide supplemental funding for county health department violence prevention programs and services.

- City agencies should actively pursue state, federal, and private grant opportunities for public health-based violence prevention programs.

- Cities should lend technical grant writing assistance to community-based violence prevention organizations.

- City agencies should apply for grants in equitable partnership with community-based violence prevention organizations, which includes allowing partner community organizations to lead while providing them with the tools and support needed for grant management and compliance.

Long-Term Violence Prevention Infrastructure

City officials should establish a permanent office of violence prevention (OVP) charged with developing and implementing a whole-of-government public health approach to violence prevention. OVPs should be established through the relative permanence of local ordinances when possible and should be vested with the legal authority to develop, coordinate, and lead violence prevention efforts across city agencies and in close partnership with community-based organizations. OVPs should also have the legal and organizational ability to quickly fine-tune strategies and programs to respond to often fast-changing violence dynamics in affected communities. Lastly, cities should have city-level OVPs, even when a county-level office of violence prevention exists.

School-Related Policies and Initiatives

Although most school-related violence prevention programs and policies are outside of the direct control of city government, cities still have a role to play when school boards fail to act. If school boards refuse to enact vital school suicide prevention policies and programs or fully inclusive anti-bullying policies, municipal officials should engage directly with school board members and school superintendents to advocate for action.

Local Firearm Laws and Regulations

In the U.S., the vast majority of homicides (nearly 80%) and the majority of suicides (53%) involved guns in 2020.[13] Violence prevention efforts, therefore, must involve commonsense gun safety laws and anti-gun-trafficking efforts.

Although the majority of states restrict cities from regulating firearms to varying degrees, local leaders still have options. Mayors and city council members, for example, can use the visibility and influence of their offices to publicly advocate against these state-level restrictions and urge their state and the federal government to enact gun law reforms. The VPI recognizes this public advocacy by city officials through partial credit in the Ghost Gun Prevention Ordinances and Background Check and Permit-to-Purchase Requirements scorecard criteria. Additionally, because these state restrictions limit many cities, cities are not penalized for not having these laws.

Finally, when it comes to addressing the role of firearm trafficking in deadly gun violence, cities have full authority to develop and lead interagency anti-gun-trafficking initiatives that focus on stopping traffickers and dealers who divert legally purchased firearms into illegal streams of commerce.

Standards for Credit

All of the policies, programs, and services detailed herein should be designed, implemented, and evaluated with equity, intersectionality, anti-racism, and the unique needs of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) communities, immigrant communities, LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) communities, and people living with disabilities as foundational guiding principles and frameworks.

Intervention and Risk Factor Reduction

Intervention

Outreach-based violence intervention programs (OVIP), also known as street violence intervention programs, are programs that employ people who live in or come from impacted communities to conduct direct street-level outreach and conflict mediation, negotiate cease-fires, and attempt to shift the culture of conflict resolution with those at the highest risk of violence. OVIP workers build strong relationships with community members most impacted by violence and leverage those relationships to help prevent violence. OVIPs should be included in OVPs’ strategic plans (assessed in the Office of Violence Prevention section below).

Localities that meet this standard are granted four points.

Hospital violence intervention programs (HVIPs) help interrupt cycles of violence by bringing trauma-informed victim and survivor services to violently injured individuals and their families or social circles in the hospital setting. HVIPs link victims and survivors of violence to community-based services and help ensure their long-term well-being through ongoing case management. HVIPs can originate within hospitals and trauma care centers, or hospitals and trauma care centers can contract with community-based organizations to provide HVIP services to violently injured patients.

Localities should fund HVIPs and implement policies and programs to encourage hospitals and trauma centers to develop HVIPs. HVIPs should be included in OVPs’ strategic planning (assessed in the Office of Violence Prevention section below).

Localities receive four points for funding HVIPs.

Cognitive behavioral therapy-integrated mentorship programs link at-risk individuals to mentors from their community who have similar lived experiences and provide individual attention and assistance, wraparound services, and behavioral therapeutic practices to help shift the behavior and, in turn, lifestyle of those most at risk of violence.

Local governments should ensure sufficient funding for community-based cognitive behavioral therapy-integrated mentorship programs, and OVPs should include these programs in their strategic planning (assessed in the Office of Violence Prevention section below).

Localities that fund community-based cognitive behavioral therapy-integrated mentorship programs for at-risk individuals will receive four points.

Victims and survivors of firearm-involved and other types of violence should have quick access to holistic services, including related medical care, mental health care, legal aid, and assistance with state crime victim compensation program claims. Moreover, coordination of care services is vital to helping victims and survivors navigate the complexities of obtaining these services from multiple providers and encouraging continuity of care. As an overwhelming number of people who are shot are killed or reinjured within five years, adequate services drastically decrease chances of retaliation and increase the odds of a healthier recovery for those most at risk of being reinjured or killed by violence.

Local governments should fund community-based victim and survivor services, and OVPs should account for these services in their strategic plans (assessed in the Office of Violence Prevention section below).

Localities that fund community-based victim and survivor services will receive four points.

Note: This category will not be assessed in this inaugural report but will be included next year.

Inadequate and inconsistent funding undercuts community violence intervention and prevention efforts. Municipal funding levels for community violence intervention and prevention strategies must keep pace with the needs and population size of those most at risk, the severity of violence, and the diverse scope of violence in a particular locality. In other words, localities must consistently invest in community-based solutions to violence in a way that is responsive to and commensurate with violence levels and dynamics. Ample funding allows community violence intervention organizations on the front lines of violence interruption to obtain the resources needed to engage an impactful number of those most at risk of violence and, in turn, save more lives.

If a locality’s total funding for community violence intervention programs (based on a review of their most recent approved municipal budget) does not meet a relative minimum funding threshold (which is based on violence levels specific to the locality being assessed), five points will be deducted from the municipality’s overall score.

Risk Factor Reduction

The ongoing mass incarceration crisis that disproportionately targets and harms Black and Brown communities contributes to and exacerbates many of the root causes of cyclical violence. While advocates continue to fight against this grave injustice, communities must ensure that those leaving incarceration who are at risk of violence have enhanced, tailored services available to assist with their transition into the community and to reduce their risk factors. These services should begin well before an individual’s earliest possible release, continue on a long-term basis thereafter, and be comprehensive in nature — including intensive case management and assistance with family reunification, housing, public benefits, employment, education, health care (including behavioral and mental health care), and legal aid.

Localities should directly provide or contract with community-based re-entry programs and services that are specifically tailored for returning residents at high risk of violence. These re-entry programs and services should be included in an OVP’s strategic plan (assessed in the Office of Violence Prevention section below).

Localities that directly provide or contract with community-based re-entry programs and services for at-risk individuals will receive three points.

While most criminal laws are state and federal laws, many municipal-level criminal laws exist that carry the possibility of incarceration. Municipalities, therefore, play a role in the above-mentioned mass incarceration crisis that disproportionately harms Black and Brown communities and contributes to the root causes of violence. These local criminal laws are enforced by municipal attorneys and municipal court systems.

In addition to changing municipal laws that contribute to mass incarceration, local officials should work with municipal attorneys and the municipal court system to implement diversion programs specifically for individuals at risk of violence that provide alternatives to criminal prosecution and incarceration, which can increase risks of violence. These programs should target those at high risk of violence and connect them to long-term, comprehensive community-based violence prevention services and supports.

Localities that implement municipal diversion programs for at-risk individuals will receive three points.

Restorative justice programs can help localities do their part in reducing their contributions to mass incarceration, while also mitigating the more immediate risk of retaliatory community violence. Local restorative justice programs provide alternatives to criminal prosecution and promote community healing by emphasizing accountability and the reparation of harms caused by crimes. These programs are contingent on the consent of victims and survivors, their families, and the offender’s acknowledgment of responsibility and harm done to victims, their families, and the community.

Restorative justice programs should be implemented and utilized when appropriate by municipal attorneys and municipal courts in the same way more traditional municipal diversion programs are implemented and used: as an alternative to criminal prosecution under local laws and incarceration in local facilities. Moreover, restorative justice programs should cover appropriate cases that involve both juveniles and adults.

Localities that implement and utilize restorative justice programs will receive three points.

People at high risk of experiencing violence should be able to quickly access safe emergency and transitional housing. This includes people who are at risk of intimate partner violence (discussed more in the Intimate Partner Violence Prevention Programs section below) and group-involved violence, as well as individuals experiencing homelessness who are at high risk of experiencing violence. It is vital that these emergency and transitional housing programs be equipped to help participants obtain permanent affordable housing and connect them with holistic long-term community-based violence prevention services.

Localities that directly provide or fund community-based emergency and transitional housing programs for people at risk of experiencing violence will receive three points.

Addressing the Root Causes of Violence

Housing and Food Insecurity

Housing and food insecurity makes it nearly impossible for individuals to overcome the various root causes of violence, like lack of employment opportunities, educational opportunities, and trauma-related health care. What’s more, many existing programs and services designed to reduce community violence are inaccessible to at-risk individuals who lack permanent housing due to application and other administrative requirements. All community violence prevention programs and services should be designed to be accessible and responsive to the needs of people who are at risk of violence and who are also experiencing housing and/or food insecurity.

Municipalities that fund long-term housing and food assistance programs that are specifically targeted to communities highly impacted by violence will receive three points.

Employment

Strategic workforce development programs targeted to youth, adults, formerly incarcerated individuals, and justice-involved individuals who are at risk of committing or being a victim of violence play an important role in community violence prevention. Over the long term, these programs support entire communities that are most impacted by violence, helping address factors related to many of the interconnected root causes of violence, including lack of access to jobs and educational opportunities, housing and food insecurity, and inadequate health care. Moreover, summer youth employment programs for at-risk youth should be a distinct part of these strategic workforce development programs. OVPs should include strategic workforce development programs for communities highly impacted by violence in their strategic plans (assessed in the Office of Violence Prevention section below).

Localities that fund strategic workforce development programs for youth and adults at risk of violence will be granted three points.

Local ban-the-box ordinances, sometimes known as fair chance ordinances, seek to discourage employment discrimination against individuals with prior justice system involvement by prohibiting employers (including the municipality itself) from asking about criminal records on job applications, deferring this inquiry to later in the hiring process.

Localities that have ban-the-box ordinances that cover both the municipality and private employers within the municipality will receive three points. If a local ban-the-box ordinance covers private employers within municipal limits but does not explicitly cover the municipality’s own employment practices, only two points will be granted. Lastly, policies that only cover municipal employment practices will receive one point.

Education

Safe passage programs help young people in communities highly impacted by violence navigate to and from school safely. These programs assemble community volunteers, school personnel, and other local officials along highly utilized school routes when students are traveling to and from school to ensure that their journeys are violence-free.

Three points will be granted if localities and/or school districts within a municipality fund safe passage programs in communities highly impacted by violence.

Comprehensive school-based violence prevention efforts include several components: (1) year-round violence prevention education and skills training for all students; (2) targeted services for students at the highest risk of violence; (3) professionally facilitated student conflict mediation; and (4) connections to school and community-based long-term services to reduce risk factors. These programs should be inclusive of and accessible to all students, including those living with disabilities or those whose primary language is not English. Additionally, any school-based violence prevention program should avoid reliance on the criminal justice system and take great care to avoid potentially discriminatory impacts.

If all school districts that serve students in a rated locality implement school-based violence prevention programs, or if a city directly funds these programs, three points will be granted.

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), suicide was the second-highest leading cause of death for youth between 6 and 18 years of age nationwide in 2020.[14] School districts must prioritize suicide prevention by enacting comprehensive suicide prevention policies mandating school-based suicide prevention programs that are continually assessed for alignment with evidence-based best practices. Moreover, school districts must follow through on their policy commitments by consistently allocating ample funding for school suicide prevention programs and personnel.

Three points will be granted if all school districts within a municipality have comprehensive suicide prevention policies and all school districts within the rated municipality have active, comprehensive school-based suicide prevention programs.

Bullying can start or feed cycles of violence in schools. School boards should adopt comprehensive anti-bullying policies that expressly protect students from bullying on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, disability, sexual orientation, and gender identity. Furthermore, anti-bullying policies should extend to cyberbullying and should rely on alternative disciplinary measures that do not push students into the criminal justice system.

Three points will be granted if all school districts within a municipality have comprehensive, enumerated anti-bullying policies.

Health

Local health departments are tasked with protecting the health and well-being of the communities they serve by utilizing evidence-based approaches to prevent disease, illness, and injury — including the injuries and harms engendered by community and other types of violence. Compared to their federal and state-level counterparts, local health officials have the added benefit of being in closest proximity to the communities they serve, allowing them to better understand their communities’ unique needs and develop the most effective public health solutions.

In coordination and cooperation with their local OVP (if established), local health departments should utilize their public health expertise and resources to develop and implement culturally appropriate violence prevention strategies that have the best chances of success in their target communities.

If a city does not have its own public health department and utilizes its county health department, city officials should work with county health officials to ensure that they develop and implement public health approaches to violence prevention.

If the public health department that serves a locality meets this standard, the locality will receive three points.

Trauma recovery centers (TRCs) provide no-cost comprehensive wraparound care to victims and survivors of violence in unserved and underserved communities. They utilize culturally competent assertive community outreach to reach victims and survivors in harder-to-reach communities, employ multidisciplinary professional staff (including psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and outreach workers), and provide trauma-informed mental health care and individualized case management (including help with housing, food, clothing, financial, and legal assistance). TRCs can be housed by community-based organizations, universities, and hospitals.

Municipalities that fund trauma recovery centers that serve victims and survivors of violence in underserved communities will receive three points.

Communities impacted by high levels of violence should have easy access to long-term trauma-informed mental and behavioral health programs to address the role that trauma plays in increasing risks of violence and perpetuating cycles of violence. These programs should be available to all at-risk individuals, regardless of insurance status or ability to pay, and mental and behavioral health services should be provided by highly qualified behavioral and mental health professionals who specialize in trauma-informed care, including addressing intergenerational trauma.

Municipalities that fund trauma-informed mental and behavioral health programs targeted to communities highly impacted by violence will receive three points.

All too often, pleas for emergency assistance by people experiencing mental health crises and their families are not met with the appropriate responders, increasing risks of violence and forcing people experiencing mental health crises into a criminal justice system further unequipped to provide the care they need. Municipalities should create a real-time behavioral and mental health crisis response system in line with the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s best practice toolkit.

Localities that create a municipal-wide, real-time behavioral and mental health crisis response system that relies on mental health professionals will receive three points.

State crime victim compensation programs are designed to reimburse crime victims for crime-related expenses, including medical costs, funeral and burial costs, and lost wages. In practice, many of these state programs are inaccessible to victims and survivors due to inequitable requirements, including overly narrow application windows and arbitrary, subjective requirements that victims cooperate with law enforcement. Additionally, the maximum reward amounts under these state programs are often insufficient to cover all crime-related costs.

For these reasons, municipalities should create local supplemental violent crime victim compensation programs for victims who are denied or granted insufficient funds by their state victim compensation program. Grants under these local supplemental programs should avoid the aforementioned shortcomings of state victim compensation programs and should minimally cover violent crime-related medical and funeral and burial costs.

Municipalities that create supplemental violent crime victim compensation programs that meet the above criteria will receive three points.

Trauma center deserts refer to regions within municipalities that have low geographic access to trauma centers, meaning the time it takes victims of the most severe cases of violence to reach a trauma facility capable of treating their life-threatening injuries is unacceptably — and in some cases, fatally — long. In communities highly impacted by violence, the proximity of trauma care centers is a matter of life and death.

Municipalities should immediately begin to develop and implement short- and long-term strategies to eliminate trauma center deserts in communities most impacted by violence. Local officials should work closely with city and county health departments and hospitals to identify and implement solutions. Moreover, municipalities should review local zoning laws and amend those that may be contributing to the problem. Lastly, local officials should also lobby state officials to develop and implement state-level solutions.

Municipalities that have developed and begun implementation of immediate and long-term plans to create more trauma centers in and near communities most impacted by violence will receive three points. If local officials publicly advocate for state-level solutions, partial credit may be granted.

As noted in the previous section, time is of the essence for victims of violence. The longer it takes a victim to reach a trauma care facility properly equipped to handle their injuries, the more unlikely they are to survive. Moreover, higher-quality Emergency Medical Services (EMS) care increases trauma victims’ chances of survival. This is why EMS response times to communities highly impacted by violence and their quality of care for victims of violence should be a primary and ongoing focus of local officials.

Municipalities should explore measures they can take on the local level to improve EMS quality and response times in communities that experience the highest levels of violence, including supplementing county EMS services with city EMS services, utilizing city firefighters as supplemental EMS responders in highly impacted communities, incorporating strong and clear quality standards and audits into EMS provider contracts, and increasing the use of data and technology to improve logistics (e.g., moving ambulance locations around based on data signaling when and where violence is most likely to occur).

Localities that undertake concrete and ongoing steps to improve EMS quality and response times in communities highly impacted by violence will receive three points.

Youth and Families

Communities impacted by high levels of violence should have access to evidence-based youth and family violence prevention programs that are comprehensive and address all forms of violence between family or household members. These programs should be proactive, community-based, trauma-informed, and culturally competent. They should incorporate education and awareness campaigns, free access to family and group behavioral and mental health care, coordination of care services, and linkages to survivor services. Moreover, these programs and services must be targeted to communities and families that are most at risk of violence.

Municipalities that fund community-based youth and family violence prevention programs and survivor services will receive three points.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) refers to all forms of violence that occur in the context of a romantic relationship, including violence between current and former spouses and dating partners as well as teen dating violence. Community-based IPV prevention programs are an important component of comprehensive violence prevention strategies.

Municipalities should fund IPV prevention programs that target those at highest risk of IPV and incorporate the following CDC-recommended strategies: teaching safe and healthy relationship skills; engaging influential adults and peers; disrupting developmental pathways toward IPV; creating protective environments; strengthening economic supports for families; and supporting survivors to increase safety and lessen harms.

Localities that fund community-based IPV prevention programs will receive three points.

Local Firearm Laws and Regulations

While communities continue to advocate for changes on the state and federal levels to halt the proliferation of ghost guns, municipal officials should work to address this issue locally and add their voice to state and federal advocacy efforts.

Ghost guns refer to unserialized, privately made firearms (including 3D-printed guns and unserialized gun assembly kits) that attempt to exploit loopholes in state and federal laws to avoid being tracked. Violent crimes involving the use of ghost guns are difficult to solve because of the untraceable nature of these firearms.

Municipalities should, to the greatest extent possible under state law, enact local ordinances that aim to prevent the possession, use, sale, and transfer of any unserialized firearm.

Municipalities that enact local ghost gun prevention ordinances will receive three points.

If a municipality is prohibited from enacting these ordinances under state law, partial credit may be granted if local officials (including mayors and city council members) publicly advocate for state-level ghost gun prevention laws and/or removal of state-level restrictions on their local authority to enact ghost gun prevention ordinances.

Since some localities do not have sufficient legal authority to enact ghost gun prevention ordinances, the points in this section are not required to obtain a top score on the Violence Prevention Index.

Current federal law contains large loopholes in background check requirements for firearm purchases. While federal law requires federally licensed firearm dealers to conduct pre-sale and pre-transfer background checks, this requirement does not currently apply to private sellers (including sales at gun shows and private online sales). If it is within their local authority, municipalities should enact ordinances requiring successful completion of background checks through a licensed dealer or local agency for all firearm sales or transfers within municipal limits (including private party transactions).

Furthermore, to the extent possible under state law, municipalities should enact permit-to-purchase rules that require prospective firearm buyers to obtain a local permit before they can purchase a firearm. Purchase permits should only be granted after successful completion of background checks and courses on safe and responsible firearm ownership (including safe storage practices) and firearm laws. Purchase permitting processes may further require minimum waiting periods and proof of residency.

Lastly, local officials should utilize their voice and platforms to advocate for these changes on the state and federal levels.

To gain three points in this section, rated municipalities must have a local ordinance requiring the successful completion of background checks for all (including private) sales and transfers of firearms, or a local ordinance implementing purchase-to-permit requirements that incorporate the aforementioned background check requirements.

If a municipality is prohibited from enacting these ordinances under state law, partial credit may be granted if local officials (including mayors and city council members) publicly advocate for state-level background check and permit-to-purchase laws and/or removal of state-level restrictions on their local authority to enact background check and permit-to-purchase ordinances.

Since some localities do not have sufficient legal authority to enact these types of ordinances, the points in this section are not required to obtain a top score on the Violence Prevention Index.

Gun trafficking refers to the diversion of legally purchased firearms into illegal streams of commerce. This can happen through means that include straw purchasing (when a person legally buys a gun for someone who is prohibited from purchasing or possessing one), purchases made through background check loopholes in state and federal law, and theft of legally obtained firearms. Municipalities should implement effective anti-gun trafficking initiatives to curtail firearm trafficking in their communities. This will require cross-jurisdictional collaboration, including cooperation with state and federal authorities. For municipalities that are not prevented from doing so by state law, these measures could also include local laws that increase safeguards against straw purchases and require the reporting of lost or stolen firearms to local authorities. Importantly, anti-gun trafficking initiatives must be data-based and focused on traffickers and dealers; they must not be used to justify wholesale overpolicing of marginalized communities and racial profiling, and should not result in racial discrimination or disparate impacts.

Municipalities that undertake concrete local anti-gun trafficking initiatives will receive three points.

Crime Reporting and Data

The effective investigation of violent crimes can help interrupt cycles of violence by reducing risks of retaliation. Clearance rates (sometimes called closure rates) are used to assess the effectiveness of law enforcement investigations. They indicate the percentage of crimes that are “cleared” by law enforcement agencies through arrest or other means.

Despite large budgets often in the hundreds of millions and sometimes billions, local law enforcement agencies across the country continue to have unacceptably low clearance rates for violent crimes, including homicides. Local law enforcement agencies should implement the internal changes necessary to ensure a strategic and effective focus of existing resources on solving the most serious violent crimes.

Localities whose law enforcement agencies have a violent crime clearance rate above 70% for the most recent year of available data will receive four points.

The most recent FBI hate crimes data reveals an alarming reality. Hate crimes continue to rise in the U.S., and firearms continue to be widely used to inflict hate-motivated violence. While the trends are clear, national hate crimes data is woefully incomplete. Since reporting hate crimes data to the FBI annually is purely voluntary under federal law, thousands of law enforcement agencies do not report any hate crimes data at all, or inaccurately report the existence of no hate-motivated incidents on the basis of any protected characteristics year after year — a statistical improbability, especially for larger localities. Full and complete data on hate crimes gives community-based organizations, advocates, and local officials the information they need to craft and implement effective solutions.

Localities whose law enforcement agencies (1) reported hate crimes data to the FBI in the most recent FBI Hate Crime Statistics report and (2) did not report zeros across the board for the five most recent FBI Hate Crime Statistics reports will receive three points.

Local Office of Violence Prevention

Local government agencies tasked with developing and implementing whole-of-government evidence-based strategies for violence intervention and prevention are vital to reducing all forms of violence — including gun violence — in the most impacted communities across the country. These Offices of Violence Prevention (OVPs) should be established through the relative permanence of local ordinances that ensure ample funding and staffing, mandate the use of evidence-based public health approaches, and grant the legal authority and agility needed to quickly adapt community-based intervention and prevention policies and strategies to evolving community violence dynamics. It is imperative that OVPs center anti-racism, equity, and intersectionality in all aspects of their work. Moreover, OVPs must ensure that their policies and programs actively work against the mass incarceration crisis — a root cause of community violence that disproportionately harms Black and Brown communities.

Localities that have an active municipal Office of Violence Prevention will receive four points.

Local OVPs should lead the development and implementation of municipal-wide strategic plans to address violence that are evidence-based, leverage the entirety of local government and community resources, and incorporate all of the violence intervention and prevention strategies contained herein. Additionally, OVPs should consider incorporating a communities-led strategy for physical improvements to disinvested neighborhoods that are highly impacted by violence as a means of violence reduction that also addresses concerns about potential gentrification.

OVPs that meet this standard are granted two points.

Local OVPs should pursue state, federal, foundation, and corporate grant opportunities year-round for their own violence prevention efforts as well as that of community-based organizations. OVPs should provide technical grantseeking assistance to community violence intervention (CVI) organizations and apply for state and federal funding opportunities in equitable partnerships with community-based organizations. Community Justice’s grant database is a valuable resource for finding available CVI grants.

OVPs that meet this standard are granted two points.

In addition to pursuing grants and providing grant-seeking support to CVI organizations, OVPs should also serve as a grant-making body. Local legislative bodies should allocate funds for this purpose and OVPs should seek additional funds to distribute to CVI organizations. Furthermore, in order to ensure strategic, effective use of government and community resources, OVPs should coordinate the activities of violence prevention programs and services to align with their strategic plan (assessed in the Office of Violence Prevention section above).

OVPs that meet this standard are granted two points.

Effective technical assistance can be the deciding factor in whether violence intervention and prevention efforts are successful. Technical assistance includes training and support for organizational and program infrastructure development, strategic plan development and implementation, data management and evaluation, community engagement, marketing, and resource, capacity, and leadership development. OVPs should be equipped with the expert technical assistance necessary to carry out its own activities and should directly provide technical assistance to community violence intervention and prevention organizations and programs.

OVPs that meet this standard are granted two points.

It is important for OVPs to conduct or oversee regular evaluations of the quality and effectiveness of (1) their own strategic plan; (2) violence prevention programs and services provided directly through their own office and other local government agencies; and (3) community organizations that receive municipal funding to engage in violence intervention and prevention work. These regular quality reviews should assess whether the aforementioned plan, programs, and services are accurately targeting individuals and communities at the highest risk of violence, are in fact achieving equitable outcomes, and are actually reducing community violence. The CDC provides a helpful violence prevention program evaluation technical assistance package. Steps should also be taken to ensure that local government and OVP-funded violence prevention programs are utilizing their funds and resources ethically and responsibly. Moreover, because violence prevention work is people-driven, program quality and outcomes are inextricably tied to the well-being of violence intervention workers. Violence prevention organizations must prioritize their workers’ physical and mental health and well-being, both on and off the job, by providing fair compensation and comprehensive benefits.

OVPs that meet this standard are granted two points.

Feature: Dr. Shani Buggs

Prevention Begins with a Public Health Response

As the gun violence epidemic continues to ravage families and communities across America, local policymakers must not wait a single day longer to take decisive, transformational action.

In 2020, firearm violence became the number one cause of death for children and youth in the United States for the first time ever. And because of the legacy and persistence of systemic racism and anti-Blackness, Black and Brown communities continue to bear the devastating brunt of this national crisis.

For at least the past three decades, firearm homicides have been the leading cause of death for Black boys and men, and the second leading cause of death for Latino boys and Black girls and women. In 2019, the Black homicide victimization rate was nearly four times the overall homicide victimization rate and nearly seven times the white homicide victimization rate. And then in 2020, firearm homicides of Black people increased by nearly 40% compared to 2019. These statistics represent thousands of loved ones, family members, and neighbors whose lives were violently cut short. Yet they can obscure the tens of thousands more Americans who have suffered from nonfatal shootings, or who witness violence by seeing someone harmed or hearing gunshots on a far-too-regular basis.

As a leading public health researcher, I can say without a doubt that violence is a preventable phenomenon. The violence that plagues predominantly low-income Black and Brown communities today is a symptom of continued systematic exclusion from the economic opportunity, reliable protection, stability, and well-being that is promised to be accessible to all Americans. This violence cannot be prevented with public safety systems designed to merely react to violence after it occurs, all while ignoring these root causes. Prevention begins with recognizing that violence is in fact a public health epidemic that demands a robust, comprehensive public health response.

Community-based violence intervention is an essential component of what a public health response to violence looks like. “Credible messengers” or “violence interrupters” — professionally trained outreach workers who hail from impacted neighborhoods and often have personal experiences with the traumas of gun violence — go out into communities to form relationships with individuals identified as high risk for engaging in or experiencing violence. Through outreach-based violence intervention (also known as street outreach), they courageously intervene in potentially violent situations to mediate conflicts, connect individuals at elevated risk of violence with services and resources, and provide mentorship and peer support. Violence intervention specialists meet victims of violence at their hospital beds to reduce the risk of retaliatory violence and connect victims and survivors to long-term trauma-informed behavioral and mental health care, financial resources, and legal aid (a model known as hospital-based violence intervention). Community-based violence intervention workers can and should also be an integral part of school-based violence prevention programs. All of these trained professionals, regardless of the settings in which they operate, have the unique ability to enter spaces, build relationships, create opportunities to link individuals to essential supports and services, and mitigate violence in ways that traditional law enforcement cannot. If elected and appointed officials are serious about reducing the violence that is harming so many residents in towns, tribal nations, and cities around this country, they must recognize that community-led strategies, like community-based violence intervention, deserve support and investment to help curb that harm and are crucial for community safety.

As with any public health response, immediate efforts like community-based violence intervention must be undertaken alongside comprehensive, long-term preventive strategies designed to address the upstream root causes of violence and prioritize healing, stability, and well-being through increased investments and structures that address the needs and priorities of families and communities impacted by violence. And all of these efforts require thoughtful data collection, research, and evaluation to ensure that we are building and expanding the very types of community safety strategies that will deliver the greatest returns on those investments.

The City Violence Prevention Index provides an important step forward in the development of a holistic framework of promising violence prevention-related policies and practices that municipal officials, local health departments, and school boards can implement without waiting on their state or the federal government. The strategies listed in the Index have already yielded encouraging results in numerous cities where they have been implemented, and they represent new opportunities to tackle violence through coordinated and multipronged approaches. With community-based violence intervention funding from the historic Bipartisan Safer Communities Act set to soon be distributed, alongside previous allocations of American Rescue Plan Act funds that the Biden Administration encourages jurisdictions to use for violence intervention and prevention, this toolkit is particularly timely and worthy of thoughtful consideration.

I urge local policymakers across the country to act decisively to invest in developing and implementing the myriad strategies included in the City Violence Prevention Index with urgency, sufficiency, and longevity. Lives, families, communities, and our collective future hang in the balance.

Dr. Shani Buggs

Assistant Professor, Violence Prevention Research Program, University of California, Davis

City Scorecards

- Atlanta, Georgia

- Baltimore, Maryland

- Baton Rouge, Louisiana

- Birmingham, Alabama

- Buffalo, New York

- Charlotte, North Carolina

- Chicago, Illinois

- Cincinnati, Ohio

- Cleveland, Ohio

- Columbus, Ohio

- Dallas, Texas

- Denver, Colorado

- Detroit, Michigan

- Durham, North Carolina

- Fort Worth, Texas

- Fresno, California

- Houston, Texas

- Indianapolis, Indiana

- Jackson, Mississippi

- Jacksonville, Florida

- Kansas City, Missouri

- Las Vegas, Nevada

- Little Rock, Arkansas

- Los Angeles, California

- Louisville, Kentucky

- Memphis, Tennessee

- Miami, Florida

- Milwaukee, Wisconsin

- Minneapolis, Minnesota

- Mobile, Alabama

- Montgomery, Alabama

- Nashville, Tennessee

- New Orleans, Louisiana

- New York City, New York

- Newark, New Jersey

- Norfolk, Virginia

- Oakland, California

- Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

- Orlando, Florida

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Phoenix, Arizona

- Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- Portland, Oregon

- Richmond, Virginia

- Rochester, New York

- San Antonio, Texas

- Shreveport, Louisiana

- St. Louis, Missouri

- Toledo, Ohio

- Washington, D.C.